I’m seeing my doctor tomorrow, reluctantly. For the last six days I’ve had increasingly debilitating pain in the right side of my lower back, into the top of my ass. I limp and hobble wherever I go, and I go out less with each passing day. Today my left leg has felt very weak, as if it might give out. I feel concerned—because I’m a hypochondriac—that I have a tumour. I try not to research the symptoms, but when I do, the internet says I have a herniated disc/pinched nerve in my lumbar spine. Lumbar radiculopathy, which is the cause of sciatica. Apparently runners get this. I run. This sounds right, makes sense, but I’m not convinced.

The person in chronic pain is exhausting. The person in chronic pain is always exhausted.

Something just like this happened when I was thirty-six. I woke up one late winter day with horrible pain in my back, and tingling in my chest. I was nauseous, and dizzy. My doctor ordered an MRI. Apparently I had a herniated disc in my thoracic spine. Thoracic radiculopathy. I looked it up online, and the symptoms described my experience. If I didn’t feel better in six weeks, I’d be referred to a surgeon for a discectomy, a gruesome ordeal involving the removal of the bony arch at the back of the vertebra. This didn’t scare me as much as I thought it might. At least it wasn’t a tumour. Nothing scares me more than cancer, not even Slenderman.

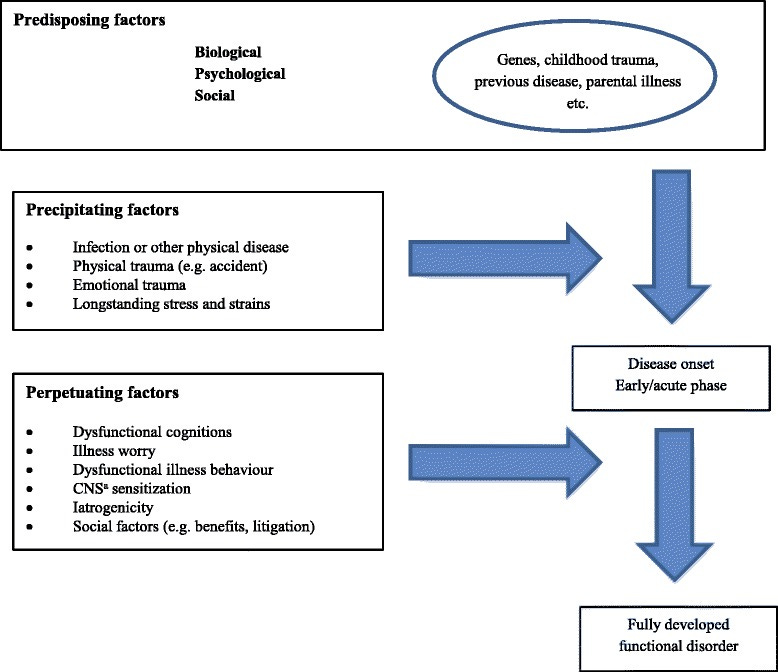

Days later I shared my diagnosis with my friend Navdeep. His eyes lit up. His mother had gone through something similar, and cured herself without being sliced open. Navdeep told me about the work of Dr. John Sarno, who wrote the bestseller Healing Back Pain: The Mind Body Connection. Sarno had been a professor of rehabilitation medicine at New York University, and wrote numerous books about his belief that ninety-nine percent of all back pain—really most chronic pain, along with eczema, fibromyalgia, interstitial cystitis, heartburn, migraines and more—was the result of repressed emotions, particularly rage. Sarno theorized that the mind protects its owner from overwhelming emotion by creating pain as a distraction. The mechanism for the pain, decreased blood flow to the afflicted area, he called Tension Myositis Syndrome, or TMS.

I was astonished by the book Navdeep’s mother credited for her good health. Sarno claimed—and this has been validated by recent studies—that herniated and bulging discs are extremely common, and totally normal; the predictable result of wear and tear in aging bodies that have been lugging themselves around—as mine had—for decades. If one hundred people my age were subject to an MRI of their spine, ninety percent would show bulging and herniated discs, yet only a small percentage would have the debilitating pain I was experiencing. Healing Back Pain describes one elderly woman with multiple bulging and herniated discs who had no complaints. If, Sarno claims, a herniated disc is the cause of numbness and extreme pain, then ninety percent of people should be bedridden, as I was, but that’s not the case.

I always thought I was special, and now I knew why. The difference between myself and the pain-free old lady with the back like a broken piano was that I didn’t express my emotions. I knew this about myself. Sarno outlined the personality type of a typical TMS sufferer, and I checked most boxes.

Perfectionism. Sarno asked if I prioritized completing tasks over my own well-being and emotions. I did. Did I have an unyielding expectation that everything I do must be perfect? Yes again. Did I always have a task that needed to be completed? Yup.

What Sarno called Goodism. Did I tend to do what others wanted when making plans rather than assert my own preferences? Yes.

Low self-esteem. C’mon.

Stoicism. Unceasing yesses. I find it challenging to communicate my emotions to others. I worry others might view me negatively if I express emotions openly. Then came the big one.

Anxiety and Fear. Did I experience fear and apprehension when my loved ones were out of sight, concerned something bad might have happened to them? Yeah, but that just means I love them. When visiting a doctor did I worry about being diagnosed with a severe medical condition, even for minor ailments? Of course, that’s the doctor’s job. Any possible way that anxiety can manifest, I’ve got it.

Sarno’s treatment plan is simple. Believe wholeheartedly that your body is safe, that you aren’t injured, and that you have repressed emotions you need to access. Journal about those emotions. Resume physical activity. Treat only your mind, not your body. It’s not an easily adhered to prescription, because the brain can be very convincing in the pain it creates, which seems to burrow into places that correspond with actual bodily abnormalities, like herniated discs. Any reasonable person shown MRI results indicating a herniated disc—accompanied by their doctor’s assertion that their problem is physical, not emotional—would struggle to discount so much evidence and remain convinced they were just angry at their father, or their spouse. Luckily for me, I’m not a reasonable person, despite being very ordinary. After reading Sarno’s book straight through twice over, my pain vanished, as did the tingling in my chest, the nausea and the dizziness. Sarno believed that some people only need to learn of his theory to be permanently cured, while others must constantly remind themselves that their body is safe. I was not one of the fortunate, permanently cured. Since discovering Sarno, I mention his theories each time I see a new physiotherapist or allopathic doctor for some ache or pain. Most of the time they’ve never heard of him, but the few times they have, they tell me it’s quack science. Recently, Dr. Wah Lee, a physiotherapist on Elizabeth Street here in New York, told me Sarno was a laughingstock, and suggested I was nuts for thinking my debilitating neck pain could be the result of repressed emotions. He said it was nonsense, then pierced me with a dozen small needles, as if that was a logical, scientific way to treat my pain.

People who claim Dr. Sarno’s books cured them of their chronic, seemingly incurable pain:

Larry David, Howard Stern, Jerry Seinfeld, Anne Bancroft and…Joe Rogan.

In 2021 I was diagnosed with somatic symptom disorder (SSD) at St. Joseph’s Health Centre in Toronto. Wikipedia defines SSD as “one or more chronic physical symptoms that coincide with excessive and maladaptive thoughts, emotions and behaviours connected to those symptoms.” A listed cause is “a heightened awareness of sensations in the body, alongside the tendency to interpret those sensations as ailments.” It says that “these symptoms are not deliberately produced or feigned, and may or may not coexist with a known medical ailment.”

I identify with all of the above. SSD is primarily about a person’s excessive, disproportionate focus on their physical sensations, and veers into hypochondria, which I also have. Hypochondriasis (now called illness anxiety disorder) doesn’t require actual pain or illness that’s overly concerning to the sufferer, it only requires the fear of serious illness, whereas SSD requires inexplicable genuine physical pain that’s regarded with more fear than is reasonable. Other terms for the aches, pains and various afflictions experienced by people with SSD are ‘medically unexplained symptoms, or MUDs’, functional symptoms, and psychogenic pain. These diagnoses typically describe just a handful of symptoms, amongst them back pain, headaches, gastrointestinal problems, genital pain and fatigue. Both irritable bowel syndrome and fibromyalgia are increasingly believed to be illnesses of psychological origin. Conversion disorder (functional neurological symptom disorder) has been around for a long time, and describes abnormal sensory experiences during times of high psychological stress; typically numbness, blindness, paralysis or convulsions. None of these labels or manifestations of pain via repressed emotion are related to factitious disorders (Munchausen’s and Munchausen’s by proxy), or malingering (the conscious, manufactured presentation of illness for some gain). Those suffering from SSD and TMS do not want to be suffering, aren’t doing so intentionally, and don’t understand what's happening to them.

As much as I relate to the diagnosis of SSD, the listed symptomatic expressions aren’t broad enough to match my experiences. TMS is a roomier diagnosis, and allows for many more physical manifestations of emotional anguish. Alan Gordon is a physiotherapist in Los Angeles continuing Sarno’s work (substituting neuroplastic pain for TMS) and who published The Way Out: A Revolutionary, Scientifically Proven Approach to Healing Chronic Pain. He also suffered with unrelenting, migrating pain and bodily sensations, and lists many more symptoms than are included under the umbrella of SSD, including teeth pain, tinnitus (which I’ve had for thirty-two years), eczema, sciatica, temporomandibular joint pain (TMJ), dry eye, gastrointestinal reflux disorder (GERD), irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), pelvic floor dysfunction, chronic prostatitis or vulvodynia, hives and others. As an example of how the mind can create genuine experiences of pain without actual injury, Gordon references an article from the British Medical Journal that’s popular in the world of pain research.

A construction worker accidentally stepped on a large nail, which went straight through the sole of his boot. He was in excruciating pain, screaming in agony. Emergency responders rushed him to the hospital, where doctors carefully removed his boot to assess the damage. Once the boot was off, everyone was surprised to discover the nail had gone between his toes, and hadn’t pierced his skin. Despite zero physical injury, the worker felt intense, genuine pain, because his brain perceived a serious threat based on the visual evidence.

This story was important for me to read. Sarno and Gordon both reiterate that fear has an enormous effect on pain. As someone with occasionally debilitating anxiety and agoraphobia, I already knew that my fearful thinking unnecessarily created monsters in my own life. Panic attacks are a perfect example of the way the mind influences the body. Claire Weeks was an Australian doctor and writer who published multiple books on anxiety, including Peace From Nervous Suffering. Weeks describes the panic attack sufferer as a victim of their own thinking by way of two fears. Fear one is any situation the person finds distressing, and these are things a “normal” person might also dislike: being stuck on the subway in a tunnel, in a stalled elevator, in a long line, in a crowded place etc. In instances like these, even a mentally sound person might notice their heart rate increase, but for someone dealing with panic attacks, they elicit an assault from the autonomic nervous system. Once the typical flurry of anxiety symptoms appear—increased heart rate, sweating, urge to use the bathroom—fear two becomes the focus: I am going to lose control, I can’t handle the way my body feels. Fear two causes the brain to release adrenaline, and the symptoms get worse. The panic attack sufferer lives in fear of their body’s reaction to fear. They aren’t afraid of being stuck on the subway, or in a crowded place, they’re afraid of the hormones produced by their bodies when they are. This “fear-adrenaline-fear” cycle is so powerful, eventually the only solution is to never leave home. For eighteen months during high school, I was essentially housebound. I rarely attended school, and was afraid to be in a car. I was convinced that something terrible was about to happen, so I shrunk my world to a size that felt manageable. As has always been the case, the thing I feared—a non-specific abstraction that nonetheless felt specific, and unbearable—didn’t manifest. Instead, my body—the one thing I couldn’t escape—became the purveyor of unrelenting bad news.

Before calling my doctor about my current symptoms—which have since changed—I googled them. This is always a bad idea for people like me. After determining I had a herniated disc in my lumbar spine, and sciatica, I read about the condition on Reddit. People said they’d been dealing with crippling sciatica pain for years, that it was the worst experience of their lives. My pain immediately increased. This wasn’t lost on me. Fear, and the power of suggestion. The nightmare really begins here. I began arguing with myself, weighing the evidence of a physical versus a psychological reason for my suffering. It was true that I’d been running, was in bad shape, didn’t stretch, and possessed all of the physical traits of someone who might be afflicted with sciatica. But…I was also constantly anxious, very stressed out, and incapable of expressing my emotions. I’d experienced TMS type symptoms before, and possessed, according to Sarno, a classic TMS type personality. I needed it to be one thing or the other, physical or mental. I wanted to know if I should treat my body or my mind. I knew that my constant rumination and inability to make a decision was just another feature of a mind/body disorder, further serving the perverse, maladaptive technique my brain had invented to keep me from sitting with discomfort, and potentially unpleasant emotions. I still couldn’t stop.

In 2021 I was seeing a physiotherapist in San Diego on Zoom. He was an adherent of Sarno’s, and suggested that I had something called alexithymia. Alexithymia—also known as emotional blindness—is defined as “a neuropsychological phenomenon characterized by significant challenges in recognizing, expressing, feeling, sourcing, and describing one’s emotions.” I’ve always told therapists and psychiatrists that the only emotions I’m truly aware of experiencing are fear, and the lack of fear. People with alexithymia are said to have few, or limited dreams. I never remember my dreams. The physiotherapist suggested I take an online alexithymia test designed by the University of Toronto. I was shocked at some of the questions.

I am often confused about the emotion I am experiencing.

Strongly agree.

It is difficult for me to find the right words for my feelings.

Strongly agree.

I have physical sensations that even doctors don’t understand.

Strongly agree.

7. I am often puzzled by sensations in my body.

Strongly agree.

9. I have feelings that I can’t quite identify.

Strongly agree.

12. People tell me to describe my feelings more.

Strongly agree.

TWO DAYS LATER

I limped to my doctor’s office yesterday, still not convinced that the pain in my ass and back wasn’t physical. I did something I’ve done countless times before; scanned my life for instances of strange pains and sensations during times of stress and emotional upheaval.

In 1993 I was existentially bummed, and tired of my mind. One day I felt a nauseatingly sharp pain in my chest, and a clicking sensation inside my torso. It felt like someone had stapled a bag of sand to the inside of my rib cage. X-rays showed nothing, but for the better part of two years I was often bedridden, and made numerous trips to the ER. I was diagnosed first with Marfan’s Syndrome, then with Slipping Rib Syndrome. The condition vanished as mysteriously as it arrived.

In 1996 my father died suddenly. I hadn’t seen him in over a year, and the last words I spoke to him weren’t pleasant. Two weeks later, carrying a heavy bag while working as a courier, I pinched a nerve in my left shoulder. The pain was astonishing, like someone had pierced my muscle with a white-hot needle. I was given a nerve conduction test, which showed I had brachial neuritis. Doctors told me the condition should resolve in a few weeks. Two years later, the pain had come to dominate my life. Twenty-five years later I’d learn that this is classic TMS. A genuine physical injury will linger, instead of resolve normally. The more I worried that I had an intractable medical problem, the worse the pain became. Six years after the injury, after all other treatments failed, I was prescribed 120 milligrams of morphine daily, and finally found relief. In 2018 I was tired of taking morphine, tired of sweating, being constipated, and finding orgasms elusive. By this time my left arm was atrophied, and I had zero bicep or tricep muscles relative to my right arm. A doctor in Toronto slowly tapered me off morphine. I was terrified that the pain would return, but to my surprise I had no pain whatsoever.

In 2021 my best friend died suddenly. He felt somewhat like my father. Within days I had excruciating pain in both of my hands, and weeks later was limping because of a new, inexplicable pain in my right knee.

In 2010 I was living in Vancouver's skid row. My career was sliding into the toilet, and I missed my family back in Toronto. One morning I woke up completely deaf. I could hear nothing for three days, and almost shit myself at the hospital when a doctor wrote on a pad that I needed an MRI to rule out a brain tumour. The next day I had a hot shower, masturbated, and my hearing returned. I have other examples, but these seem like enough to illustrate a point.

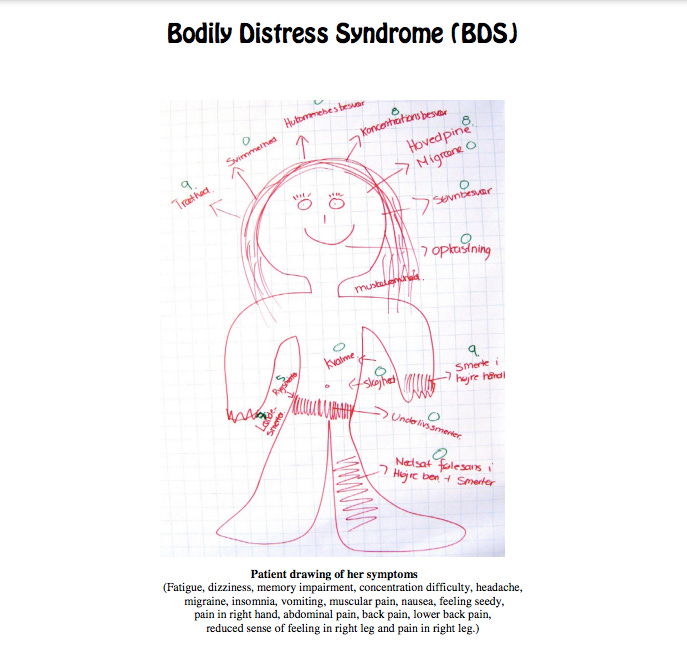

In 2016 the Somatic Distress and Dissociative Disorders working group proposed adding a new disorder to the eleventh revision of the International Classification of Diseases - Bodily distress syndrome (BDS). Finally, a syndrome I can get behind. The name alone feels satisfying. My body is, more than anything else, a source of great, unceasing distress. BDS is defined as “characterized by the presence of bodily symptoms that are distressing to the individual and excessive attention directed toward the symptoms, which may be manifest by repeated contact with health care providers. If a medical condition is causing or contributing to the symptoms, the degree of attention is clearly excessive in relation to its nature and progression. Excessive attention is not alleviated by appropriate clinical examination and investigations and appropriate reassurance. Bodily symptoms and associated distress are persistent, being present on most days for at least several months, and are associated with significant impairment in personal, family, social, educational, occupational or other important areas of functioning. Typically, the disorder involves multiple bodily symptoms that may vary over time. Occasionally there is a single symptom – usually pain or fatigue – that is associated with the other features of the disorder”

BDS allows for the entire body to miscommunicate with its owner, and for pain and unpleasant sensations to occur absolutely anywhere. There is a belief that people who suffer from somatic symptoms of psychological/emotional pain misinterpret normal sensations. This is called allodynia, which is defined as “a condition where normally non-painful stimuli, such as light touch, temperature changes or pressure, cause significant pain.” Since September of 2024, I’ve been experiencing something that sounds so insane, I’ve told almost nobody. Any time I’m laying on my back—and often when I’m sitting upright—I’m aware of the feeling of the right side of my ribcage pressing against my skin. Today I understand that this is all just anxiety, but that understanding isn’t a cure. My nervous system is primed for disaster, and in the absence of genuine threats, it manufactures them instead. My body’s normal structure, totally innocuous, has become as potentially dangerous as a fire, a tornado, a rabid dog.

I saw my doctor, Dr. Chen. She said I had all the signs of sciatica, and she didn’t seem concerned. She ordered an X-ray, and I’m waiting for the results. Walking back home from her office, I noticed that the pain had decreased. This morning the pain was almost totally gone. I swallowed a supplement with my smoothie, and felt it get stuck in my esophagus, as pills sometimes do. Since then, I’ve had an increasingly worrisome sensation in my throat, like something is stuck there. Something bad. Despite everything I know, I’m back to arguing with myself. Did I scratch my esophagus? Is it cancer? Two days earlier, I was worried about my hip. Two months before that, my neck. I don’t have a point I’m trying to prove here, I just want to share information. I know other people deal with the things that I deal with, and that like me they feel crazy, and embarrassed. Our bodies are supposed to be our friends, not strange objects we’re at odds with. If I had any advice, it would be to get in touch with your emotions. Then maybe you can tell me how you did it.

*If you experience anything like I’ve described above, you might find relief here.

Thanks for this and the links. Most of them are new to me. Been in chronic pain for years — herniated disc, nerve pain, TMJ, numbness, foot drop. Tried all kinds of solutions like massage, consulted for surgery, PT, chiro, acupuncture, culty workouts. My former therapist suggested it was psychological but never pressed the idea. Was recently thinking the acupuncture helped temporarily, prob because of the psychological barrier of accepting a foreign object puncturing the skin, lying meditating on that for 45 mins. Forcing new or changed neural paths, maybe. Feel for you. Hope you keep finding ways forward.