My previous post was something I wrote for A24 a few years ago. In the introduction I mentioned having worked on films in the mid-1990s, which I’d sort of forgotten about. I struggle to produce ‘content’ for Substack because I feel compelled to post writing that’s ‘polished’, or that argues a point. My friend Tao encourages me to be less precious, and leads by example. He recently posted this, about the feral rooster he lives with in Hawaii, and it’s very entertaining. I’m going to model myself after Tao from now on. He seems objectively more at ease than I am.

I think I started working in film in the winter of 1996/1997. The phrase ‘working in film’ makes it sound like more than it was. For three years I was ‘location security’ for a Toronto production company, and for one additional year—I think—I scouted locations for that same company as a ‘location assistant’.

Maybe it should be ‘location’s’. Look, not precious.

The production company was owned by a French woman named Jazz and her husband, who had an unremarkable name. When Jazz spoke English her Parisian accent made it sound like she was picking the words out of her teeth with her tongue.

In my capacity as security, I spent anywhere between twelve and eighteen hours per shift in a lawn chair, usually outdoors, guarding either parking spaces reserved for trailers, honeywagons1 and other production vehicles, or guarding sets. The word ‘guarding’ should be in quotations, so I’ve done just that. In 1998 I weighed—at my current height of six feet and one half inches—around 150 pounds. You’ve probably seen what happens when a movie or television show is being filmed where you live. A bunch of people in Tevas and cargo shorts appear, acting like they’re administering polio vaccines in a refugee camp. If you parked in a certain spot on your street every day for the previous six years, you’re suddenly forbidden from parking there, because Matthew Modine and Meg Ryan are in town, and the scene they’re shooting trumps the life you’re living in terms of importance. My job was to arrive in your neighbourhood the day before filming, and to place orange pylons in your parking space, and in the parking spaces of each of your neighbours. The next day I’d come back and chainsmoke in my lawn chair while reading a Milan Kundera novel (I was 23). When you came home from work and tried to park your car, I’d wave a permit in your face, and tell you to park somewhere else. Even worse, if you were walking your dog or coming home from the grocery store, I’d tell you to be quiet, that we’re shooting a scene, that it’s a ‘hot set’, and direct you to find another way home.

So I was often subject to shocking levels of verbal abuse. I was told to ‘go fuck’ myself, and I was called a ‘fuckface’ or ‘shithead’. Twice I was hit with one of the very pylons I was being paid to watch.

Here’s what I remember

.

In Toronto in the 1990s, and maybe still today, Breadalbane Street and Grosvenor between Bay and Yonge Street was where male sex workers plied their trade. A quick google search reminds me that Sneakers—a hustler bar—is in this area. Apparently Sneakers and the adjacent Burger King are still rent boy territory. I remember my friend Bruce LaBruce—celebrated gay pornographer and artist—taking me to Sneakers for a drink in 2001 with our friend Rosemary. Rosemary was overwhelmed with attention from male suitors, which Bruce explained had to do with certain male sex workers attempting to convince both themselves and others they weren’t gay. I received scant attention myself. In 1996, secondary filming for The Long Kiss Goodnight2 was being shot on Breadalbane street, and I was told to arrive on location at 7PM, and ‘guard’ parking spaces. There were no smartphones in 1996, something I feel nostalgic for the minute I remember it. I had nothing to do during these shifts except read and smoke cigarettes. As the night wore on—and I was the only security present—the aforementioned sex workers appeared. I had no idea I was on their turf. At the time, I suppose I looked somewhat like they did. Thin, fashionable, and not entirely heterosexual. I remember wondering why these bands of lithe young men kept checking me out. As I watched them leaning into the passenger windows of cars that kept circling the block, I began to understand what was happening. Somewhere around 2AM three of these young men approached me, their body language indicating they weren’t happy. They accused me of poaching their territory, and wanted to know where I got off setting up shop in a lawn chair. It took a good ten minutes of explanation for them to accept that I was there on a different job. I might have promised the more threatening of the bunch a non-speaking role in the film, a promise I had no business making. They left me alone for the remainder of my shift, during which I had to tell a handful of johns that I wasn’t available.

Later, an enormous set burned to the ground near Cherry Street, in Toronto’s east end, which led to delays in production. I heard rumours that the fire had been started by member’s of the carpentry union, who were unhappy with working conditions, or scabs, or something equally union-like.

In 1998 I worked almost exclusively on Earth: Final Conflict, a Star Trek spinoff. I spent weeks in an airplane hangar in the east end, guarding sets, and shooing away people who wanted to park their cars. One late October night, while sitting near a Taelon prison designed to break the spirit of the Ferengis, I got horny. The construction of reality in film—by props and production design—is flimsy when witnessed in person, instead of on screen. Bricks are made of what’s clearly foam spray-painted burgundy, and the magic dissolves before your eyes. In one of the cells in this Taelon prison—to signify male sexual yearning—a Hustler magazine had been placed on a cot. On screen, the magazine wouldn’t be identifiable, but the porny shapes and oily skin on the cover would sufficiently convey ‘prison porn’. Like I said, there were no smartphones. And I was 24, an age when horniness is a problem that needs to be solved, not just a vague unease. Being a lover of film—and a good employee—I wanted to be mindful of continuity. I found a roll of masking tape, and, after gingerly opening the ‘prison’ door, laid down tape along each edge of the Hustler, so that I could return the magazine to the exact same place. After eight to nine minutes in the honeywagon, I set the magazine down, removed the tape and closed the door. I can’t remember if I told my partner about it at the time, but I know she was watching the show with me the following year when I saw the blurry Hustler in the background of a scene, and felt weirdly thrilled to think of what I’d done.

What I remember is that off-duty cops—who are paid upwards of four times what they make as police officers to work on film sets—have by far the best weed that I’ve ever smoked. They also tend to tell horribly racist jokes.

Working as security, I often found myself in locations and situations where I was powerless, and uncomfortable. On these shifts, which took place during the quietest, spookiest hours of the day and night, I was usually paired with total strangers. One very cold January night, I spent eight hours inside of some dude’s Acura Integra—ostensibly guarding an outdoor boxing ring which featured in an important scene in a now-forgotten film—while he smoked crack, bragged about and fondled his illegal handgun, and told me that he’d always fantasized about killing his kids.

At this time in my life, I was obsessed with the most discordant jazz music; late John Coltrane, Pharaoh Sanders, Archie Shepp. I can’t remember the production we were on, but one night my co-worker brought up music. I think his name was Nick, and he shared my tastes. He was a jazz drummer in the vein of Rashied Ali, who played on my favourite Coltrane album, Interstellar Space. While we praised music other people equated with torture, it was revealed to us that we ‘guarding’ parking spaces in a hotspot of gang activity and drug sales. We’d been told to camp out on top of a parking structure, and to keep watch of the area beneath us. While lost in a rare moment of connection, we hadn’t noticed a half dozen men setting up shop on a picnic table adjacent to the street beneath us. This was an area of Toronto I would never walk through during the day, I told Nick, having just remembered that, and now here we were at 4AM, stoned and alone. The men beneath us, much to my shock, had handguns, some on the table and some in their back pockets, and were selling something—I assumed drugs—to customers that rolled up in cars.

“Shhhhh.” Nick said.

It was the ‘shhhh’ that fucked us. While these men hadn’t heard our conversation, they were highly alert to being shushed, and for the first time in my life a gun was pointed at my face. That they were twenty, maybe twenty-five feet away did not reassure me. Guns have a way of making things clear, and I instantly understood what these men thought. While at work doing something illegal, they’d looked over their shoulders to discover two people staring back at them, situated in a such a way that they appeared to be doing surveillance, just like cops.

“Oh. We’re cops.” I said to Nick.

“Shit yeah, we’re cops.” Nick said.

We weren’t cops of course, but that was immaterial. They aren’t really dinosaurs in Jurassic Park, but the movie’s still scary. There was something poetically job-related happening here, but I was too terrified to appreciate it. The things they yelled at us I can’t exactly remember, but I know they were scary. Nick proved to be more unflappable than me, and after a long conversation held from an almost safe distance, things calmed down. In the morning when the crew showed up, Nick spoke to craft services3, and for the remainder of the week, the men with guns ate for free.

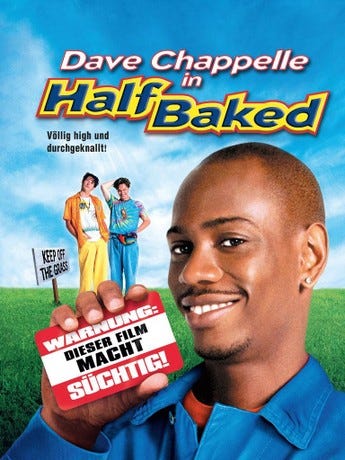

These aren’t the stories I thought I would tell about my time in showbiz. I mentioned in an earlier post working on Half Baked with Dave Chappelle. I’m not sure I knew who Chappelle was back then, not really. It sounds crazy, but at the time, his obnoxious dipshit co-star Jim Breuer was the more famous of the two. When I tell people I worked on Half Baked they expect great stories, and I understand why. But all I remember is being inside of an elevator at Mount Sinai hospital on University Avenue—where some of the movie was filmed—and taking Chappelle and Breuer up and down over and over for hours on end. I remember they laughed a lot. I remember Chappelle was short, as all actors are. My impression was that they were smoking a lot of weed, which makes sense considering the movie they were in. But today I know that Chappelle is quietly, devoutly Muslim, and as far as I know has been abstaining from everything save cigarettes for a very long time. I could be wrong.

I also worked on Dirty Work with Norm McDonald, who’s one of the few rare celebrities I truly admire, and would be starstruck to meet. Of course he’s dead now, which is sad, and makes that impossible. Artie Lange was also in Dirty Work, and of the two, Lange is the one you’d expect to be dead. It’s absurd almost, that Lange’s alive while Norm’s dead. I didn’t meet either of them when I worked on the movie. The only remarkable thing that happened is that, for reasons I can’t recall, Saul Rubinek was often on set, and despite not having a driver’s license, I twice was told to drive Rubinek’s red Lamborghini from one location to another. I did what I was told. I remember that on the second occasion, when I started his car, he’d been listening to Soul Asylum.4

Throughout my life, television and movies have been my most reliable companions. What I remember most about those years was how much I enjoyed being inside of something that had always felt both distant and familiar. I liked seeing aliens from Earth: Final Conflict drinking coffee or talking on the phone, still in costume. I liked seeing tense, sometimes violent scenes instantly become light when someone farted, or flubbed a line. I love the idea of being able to say ‘cut’ when things aren’t working. It’s something I’ve wished I could do countless times in my life.

If I had to describe the three, four years I spent working in the movies in one sentence, I’d do it like this:

“In the early morning hours, I drove around Toronto on my bike when I was supposed to be guarding a set, sometimes after having smoked a joint with a cop, or a co-worker, and it was mostly always quiet and I felt free, and I was grateful I had the kind of job I had, and sometimes I was scared, but mostly I wasn’t, and I got a lot of reading done, smoked a lot of cigarettes and met some interesting people.”

a honeywagon is a a trailer that’s a toilet, or a trailer that contains multiple toilets. It’s where actors (talent) and crew take shits, urinate, or more commonly in my experience, snort fat rails of cocaine off of baby changing tables.

with Geena Davis and Samuel L. Jackson, directed by Davis’ then husband Renny Harlin. A grossly underrated action film.

craft services = food. Craft services was the most wonderful part of working on films. Some productions had dogshit food. Television shows typically had donuts and cookies and cheap coffee, but on big movies I ate like a king. Lobster tortellini, steak, champagne.

Wikipedia - “Soul Asylum is an American rock band formed in 1981 in Minneapolis, Minnesota. Their 1993 hit "Runaway Train" won the Grammy Award for Best Rock Song.” I was shocked to learn the band formed in 1981. What were they doing for the entirety of the 1980s? Could it be worse than what they were doing in the 1990s?